The mountain problem - finding formAn artist’s surroundings can inflect their form. Consider, for instance, the effect of Rome on its resident contemporary architects, New York’s real estate market on painters, decaying furniture abandoned on the street on post-conceptual Berliners, or the soaring Alps on sculptors who live near them as Swiss artist Flurin Bisig does. But when I brought this up with him in conversation, he retorted: ‘Aren’t mountains formless?’* I had also been thinking of a mountain as an open-ended metaphor for what artists face when they try to make anything meaningful. Although, I also think he is right, in the sense that the sublime shapes found in nature differ from forms in art, which involve intention and the assertion of autonomy. This artistic autonomy, Bisig quietly claims most days through the humble discipline of making abstract drawings, despite—and because of—the mountains, both real and metaphorical, just outside his studio window in Glarus. In this ongoing series of works, drawing is the art of distilling his whole being in a moment down into a handful of intersecting weighted lines on a page.In the 20th century, as the sculpture problem continually morphed, finding new materialities, modalities and expanded forms (including formlessness), the actual mountains faded from view, or seemed less looming. And since the 1970s through the rubric of postmodernism, ‘the mountain’ that an artist like Bisig must somehow navigate is now the unstable, shifting weight of cultural histories. The burden of ‘knowingness’ on form. Thus deeply postmodern, Bisig’s recent series of collaged paper cutouts, Studies in the History and Criticism of Sculpture (2024––ongoing) hybridize or a smash-up two extremely disparate sources. On one hand, reproductions of Renaissance and Gothic sculpture, and on the other, templates drawing on vintage Donald Duck comics, thus illustrating the breadth of the challenge represented by art’s past with each filigree swoop of a scalpel. Meanwhile, sculpture has been pulled apart and reconstituted many times, while remaining a four-dimensional challenge for maker and viewer alike. I am sympathetic to the destructive impulse that flares up when faced with the past while you try to be authentic, or allow the new. This is perhaps what Bisig’s somewhat dramatic reference to the Apocalypse in the exhibition title in part refers to. Namely, the perverse wish for the freedom of a tabula rasa even in the wake of destruction.

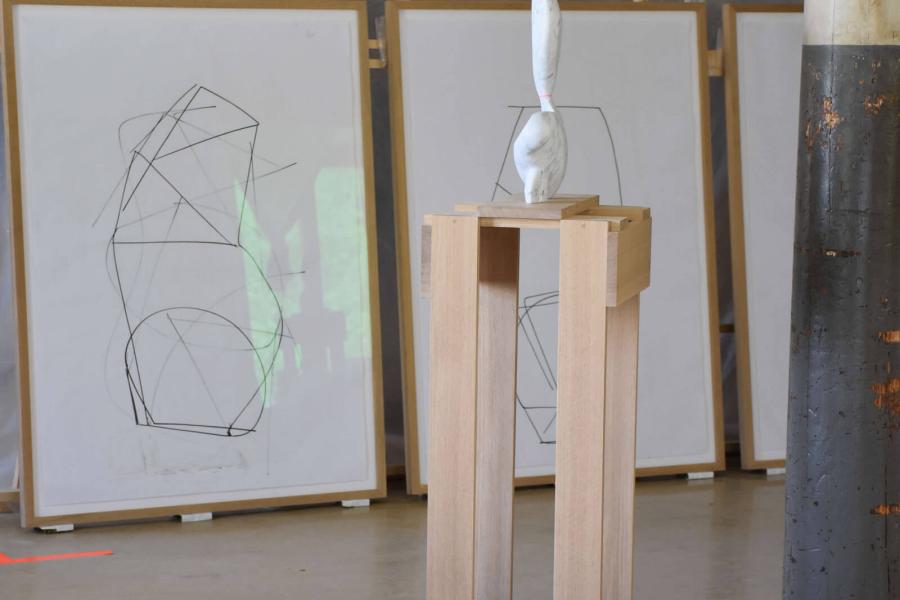

In their shape, mode of presentation, and materials, Bisig’s sculptures contain resonances and echoes of sculptural history, in particular the European modernist Avantgarde. Though not strictly referential, his work is also not forgetful. It did not surprise me to learn then that a teenage Bisig was once transfixed by an art book showing Alberto Giacometti’s studio. Seeing it, Bisig recalls having an epiphany of sorts whilst recognizing the possibility as an artist of choosing an ascetic way of life. (Trying to work out how to live is one reason for art’s existence.) In Bisig’s curvy marble manifestations, Constantin Brancusi also lingers in the peripheral vision, as do the visionary and utopian impulses of Jean Arp and his first wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp, considering also the salon-like installation of his works in the gallery. Playing a supporting role, Bisig’s see-through plinths for his marble forms were inspired by the wooden cages used for transporting blocks of marble from Carrara, but ‘translated for a gallery setting’, through fine joinery and expensive solid oak. The plinths convey the lasting value of a connection to materiality and craftsmanship. But they also suggest that sculpture is no longer monumental or stable, but a mobile commodity, and that the trading of art itself has an aesthetic that generates a mineable surplus. As emergent entities, Bisig’s anthropomorphic forms move with the perception of each viewer and their imagination. In this way, though hewn in part from a single stone quarried from a distant mountain, they have a life of their own as Pygmalion first experienced sculpture could.

Dominic Eichler

Flurin Bisig - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: gnypgallery.com

Flurin Bisig - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: gnypgallery.com Flurin Bisig - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: gnypgallery.com

Flurin Bisig - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: gnypgallery.com