David Salle Tree of Life, This Time with Feeling

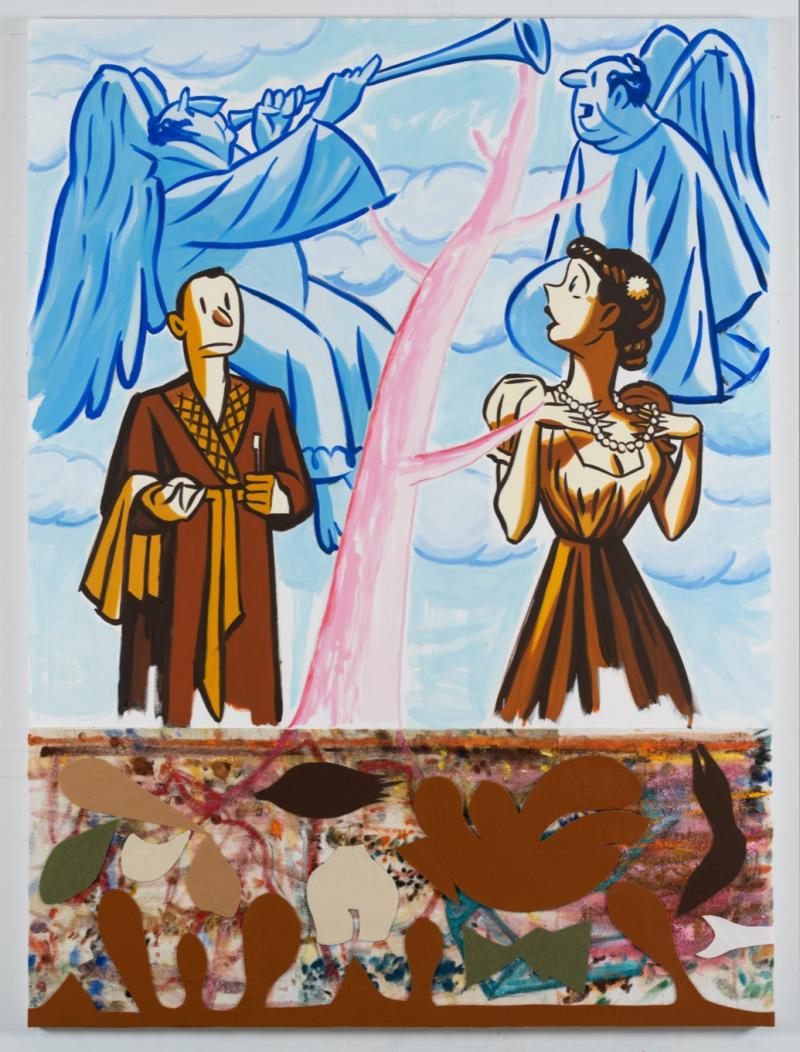

David Salle The Ladies, 2022 oil and acrylic on linen 261,6 x 248,9 cm (103 x 98 in) (DS 1156) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac

David Salle The Ladies, 2022 oil and acrylic on linen 261,6 x 248,9 cm (103 x 98 in) (DS 1156) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropacWas: Ausstellung

Wann: 21.01.2023 - 04.03.2023

Wo: Paris, Frankreich

Across the large, multipartite canvases on view, brightly coloured trees seem to grow out of subterranean painterly worlds that evoke the visual language of Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. These panels offer a distinct space for Salle to experiment with a more instinctive form of mark-making, which feeds the roots of the tree and animates the rest of the picture. ‘The art part’, as Salle calls it in a recent interview, ‘seemed to unlock some energies, some cultural forces that sparked in me a whole range of responses.’ In each one, he alternately pours, splashes and dabs paint in bright colours, sometimes overlaying anatomical sketches or Matissian felt cutouts in an experimental way that contrasts with the schematic narrative constructed in the upper sections. Invoking their predecessors found at the base of medieval and Renaissance altarpieces, Salle’s predellas represent the past, at once in a cultural, personal and art-historical sense.

In contrast to earlier Tree of Life works, the trees in This Time with Feeling are mostly bare, as though mirroring the series coming to a close. As a motif, they reverberate throughout the history of art, invoking the trees of the Garden of Eden, as depicted by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1528, or the 19th-century drawings of Shaker artist Hannah Cohoon. Trees have also often been used in attempts to draw a direct lineage from French painting to American Modern art. All of these references coalesce in the new paintings by Salle, who identifies the tree with a form of collective experience, a lineage of which we are all a part. The tree also conditions the interactions of the characters on either side, held in place as they are by the branching structure.

Viewers are encouraged to identify with stylised black-and-white figures of men and women acting out a silent human comedy in the upper part of the paintings. These are drawn from mid-century New Yorker covers by Peter Arno, whom Salle admires for his ‘ability to sell a gesture or a situation with very few brushstrokes.’ The cartoons came to define New York society from the first year of the magazine’s publication in 1925 until Arno’s death in 1968. As F. Scott Fitzgerald put it at the time: ‘Perhaps Peter Arno and his collaborators said everything there was to say about the boom days in New York that couldn’t be said by a jazz band.’

Salle re-stages Arno’s characters in his paintings, removing any captions or dialogue to allow for ambiguity and misunderstandings to arise from the looks and gestures they exchange. Men, sometimes hatted in the style of the day, and society ladies in form-enhancing dresses seem to embody the dynamic between men and women that has underlaid Western society since the myth of creation. They are mirrored in the fragmented doll-like body parts found in some of the lower sections, playing with stereotypical representations of gender. In related, art-historical terms, the scenes seem to parody the myth of creativity as stemming from an encounter between a male artist and his female muse.

Like an encore, three large square paintings at the centre of the exhibition bring together the entire cast of the Tree of Life series. The groups of characters are looked upon bemusedly by groups of animals, just as in Cranach’s famous depiction of Adam and Eve. ‘David Salle’s Tree of Life is an invitation to investigate both ignorance and knowledge, good and evil, with the necessary humour’, writes museum curator Bernard Blistène in the accompanying exhibition catalogue. With ever-more gestural markings in the lower parts, the paintings in This Time with Feeling bear witness to the cacophony of modern life, or as Blistène describes it ‘something like what the world was at its beginning and what it would have unfailingly become.’

Salle’s fractured compositions eschew any linear interpretation. The everyman and woman, represented in the Tree of Life series as types, invite viewers to project their own experience onto the scene and form their own understanding of the characters' dramatic interactions. In the same way, the multiplicity of visual references across the various components of the painting generates what the artist calls the ‘malleability of meaning’ that is at the heart of his oeuvre. The paintings are engaging without being descriptive. ‘They're like music, in a way,’ states Salle, ‘being able to identify the notes doesn’t say much about what it feels like to listen to the music.’

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue with an essay by the former director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne-Centre Pompidou, Bernard Blistène.

About the artistDavid Salle's paintings are immediately recognisable for their juxtaposition of contrasting elements drawn from his personal visual lexicon. This wide-ranging catalogue includes quotations and appropriations from art history as well as from advertising design, cartooning, and other vernacular forms of signage and communication. By combining seemingly unrelated images in diverse representational styles, Salle plays with viewers' aesthetic expectations. Using cinematic techniques such as montage and superimposition, he creates a world of simultaneity and equilibrium that privileges provocative and sometimes absurd relationships.

For Salle, painting – like poetry or language generally – has a syntax that is sometimes hidden or disguised. It involves a counterbalance of contrasting elements: 'compression, juxtaposition, simultaneity, dissonance, humour, and resistance to closure, [...] It makes free use of surprising and abrupt transitions. It seeks to distil entire blocks of emotion and complex experiences into the telling detail, the closely observed fragment that stands in for the whole.' Containing allusions to Pop art, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, as well as cartoons from the 1940s through 1960s, his works combine various iconographies and formal qualities. Their kaleidoscopic effects seem to reflect a constant stream of simultaneous thoughts and feelings, constituting a deeply sympathetic and at times ironic stance towards contemporary life and the status of painting itself.

Born in 1952 in Norman, Oklahoma, Salle lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He studied at the California Institute of the Arts from 1970 to 1975, where he was mentored by Conceptual artist John Baldessari. It was there that he first developed a strong interest in cinema and montage, as reflected in his earliest works. He came to prominence in the 1980s as a leading figure of the Pictures Generation, who questioned the status of the image through appropriation and the exploration of mass media.

Salle's first solo museum exhibition was held at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam in 1983, followed by his first retrospective in 1999 at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, which travelled to the Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna; Castello di Rivoli Museo d'Arte Contemporanea, Turin, Italy; and Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain. His work has since been shown at institutions including Musée National d’Art Moderne-Centre Pompidou, Paris; The Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others. Recent surveys of Salle’s work were held in 2016 at the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga and in 2020 at the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT. Salle is also a prolific writer and critic whose essays and interviews have been published in Artforum, Art in America, Modern Painters, The New York Times T-Magazine, and The Paris Review, as well as in numerous exhibition catalogues and anthologies. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books. His collection of critical essays, How to see, was published by W. W. Norton in 2016.

Tags: David Salle, Druckgrafik, Grafik, MalereiGALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC37 DOVER STREET, LONDON W1S 4NJ T +44 (0) 20 3813 8400 ROPAC.NETOPENING HOURS TUESDAY – SATURDAY 10 AM – 6 PM

David Salle Tree of Life Heavenly , 2022 oil and acrylic with cotton toweling and felt on linen 248,9 x 182,9 cm (98 x 72 in) (DS 1150) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac / Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Marais

David Salle Tree of Life Heavenly , 2022 oil and acrylic with cotton toweling and felt on linen 248,9 x 182,9 cm (98 x 72 in) (DS 1150) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac / Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Marais David Salle Tree of Life False Smile, 2022 oil and acrylic on linen 177,8 x 127 cm (70 x 50 in) (DS 1148) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac / Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Marais

David Salle Tree of Life False Smile, 2022 oil and acrylic on linen 177,8 x 127 cm (70 x 50 in) (DS 1148) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac / Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Marais David Salle Telephone for You, 2022 Oil and acrylic on linen Image 198,1 x 137,2 cm (78 x 54 in) Frame 204,3 x 142,5 x 6,7 cm (80,43 x 56,12 x 2,62 in) (DS 1144) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac / Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Marais

David Salle Telephone for You, 2022 Oil and acrylic on linen Image 198,1 x 137,2 cm (78 x 54 in) Frame 204,3 x 142,5 x 6,7 cm (80,43 x 56,12 x 2,62 in) (DS 1144) - Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von: ropac / Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac MaraisCopyright © 2025 findART.cc - All rights reserved